More than 2,000 years ago, a low-ranking official recorded details of his work and life spanning 14 years on bamboo slips. These journals were buried in his tomb in what is today, Shuihudi village, Yunmeng county in Central China's Hubei province. They were meant to accompany him into the afterlife.

An accidental discovery and the resulting excavation in 2006 brought these relics to light. Years of study into these records has formed a vivid impression of this Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) official, Yueren, as well as increased knowledge of the calendar system, grassroots governance and household tax at the time.

For example, Yueren had beautiful handwriting. He was literate— an essential requirement for grassroots officials— and seemed particularly good at accounting.

He had story books buried with him that could possibly have been his favorites, as well as two volumes of law codes. His work largely involved measuring land, checking the registered population and reporting on economic and social data. He had to travel a lot for work.

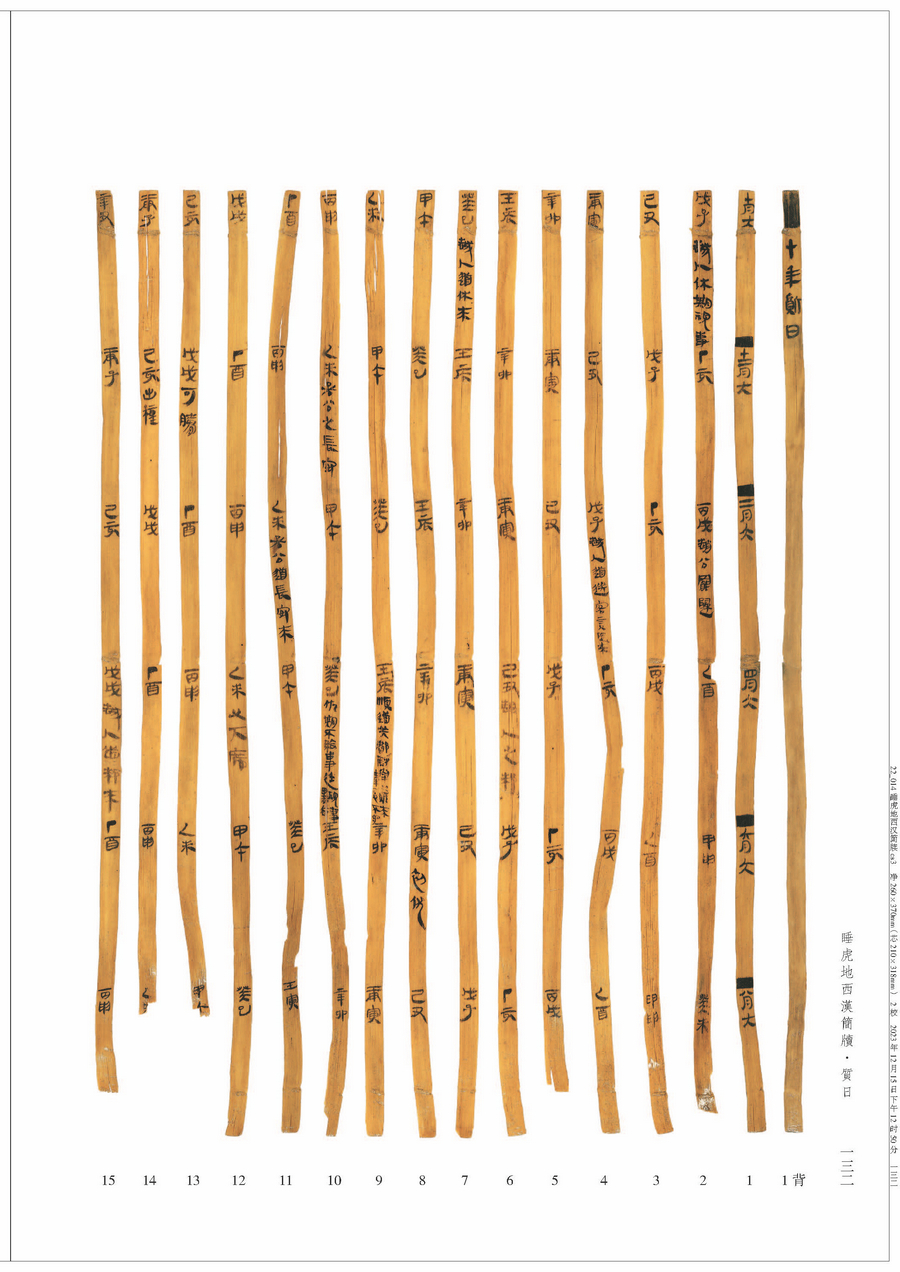

From 170 to 157 BC, during the reign of Emperor Wendi of the Western Han Dynasty, Yueren wrote zhiri, a diary form that's similar to today's calendar, marked with the dates and a small space to fill in daily schedules. One volume of the diary covers the time span of a year.

This form of record-keeping was once popular during the Qin (221-206 BC) and Western Han dynasties but is rare in literature passed down through history, according to Chen Wei, director of Wuhan University's Center of Bamboo and Silk Manuscripts.

It is via this type of unearthed bamboo slip that archaeologists and historians are able to learn about zhiri, which in the old days, was also used as a reference in assessing the performance of officials, he adds.

Wang Zijin, an expert on the history of Qin and Han (206 BC-AD 220) dynasties, says the use of zhiri embodied ancient people's understanding of time, and their awareness and skills of time management.

It reflected social order and was seen as being related to administrative efficiency, he says.

The experts were addressing an academic symposium on zhiri at Wuhan University in early January, during which paper copies of these zhiri items were launched as the first volume of Bamboo Slips and Tablets of Shuihudi Western Han Tomb.

Over the past 50 years, dozens of Qin and Han dynasties tombs have been discovered in Shuihudi. From Yueren's tomb alone— archaeologists have labeled it Shuihudi Tomb M77— more than 2,000 bamboo slips and wooden tablets written from 175 to 157 BC have been unearthed.

Apart from zhiri, the manuscripts also include content regarding math and law, as well as judicial documents on grain transport along the Yellow River.

The center intends to publish eight volumes of Bamboo Slips and Tablets of Shuihudi Western Han Tomb altogether to provide comprehensive information about the relics.

Qin Zhihua, head of the Zhongxi Book Co, the publisher of the series, says hopefully two more volumes will be released this year.

Experts estimate that Yueren's zhiri documents should have comprised around 900 slips, yet only about 700 have been discovered, apart from some that are damaged.

Chen says identifying these damaged pieces and putting them back in their original order was really a challenging but crucial step toward restoring and interpreting the texts. He says seven batches of zhiri slips have been unearthed at multiple archaeological sites across the country, making 23 volumes of zhiri altogether, among which 14 were found at Shuihudi.

Yueren's zhiri slips were woven together with three threads and read from right to left. For each year the dates started from lunar October, as it was then seen as the start of a year. There were extra slips for leap months.

The dates were pre-labeled, and Yueren only marked a small portion of the days with brief content.

During his career, Yueren served in various local departments in Anlu county and later Yangwu township, including the government, the military, and the judicial department, as well as the sector in charge of farming, land sales and agricultural tax.

He was also involved in the building of public facilities, collecting pearls, and grain transportation.

Yueren was hardworking. Several slips from April 170 BC show that he went back home upon his father's passing amid pressing affairs, and hastened back to work the day after the funeral.

"On average, he traveled 141 days for work per year. It seems common for grassroots officials at that time to spend one-third of a year taking business trips," says Kim Byungjoon, professor at the Department of Asian History at Seoul National University.

Yueren was proud of some of the tasks he tackled, such as sending the military papers and tributes of fresh food and other products to Western Han's capital Chang'an— today's Xi'an in Shaanxi province. For both urgent duties he took a carriage.

However, the official was accused and fined several times in the last three years of his career. It was not necessarily due to his own fault but might have been because of the unsatisfying overall situation of the area, according to Chen.

Yueren is believed to have passed away in 157 BC, in his 50s.

"He worked at the grassroots without promotion for 15 years. He must have been depressed with these punishments in his later years, which might have something to do with his passing," Chen says.

Historian Zhu Fenghan says that Shuihudi's zhiri slips help build a new understanding of this style of record-keeping. For example, it not only contained official affairs but also personal matters.

Yueren's zhiri slips also mentioned his mother's passing and the marriage of a female relative, who could either have been his daughter or a sibling.

According to Chen, one wooden tablet excavated from Yueren's tomb indicates that upon a female relative's passing in 175 BC, the family received donations from 81 people. In return, they sent money and gifts in the following decade to these people for funerals, marriage or journeys they undertook.